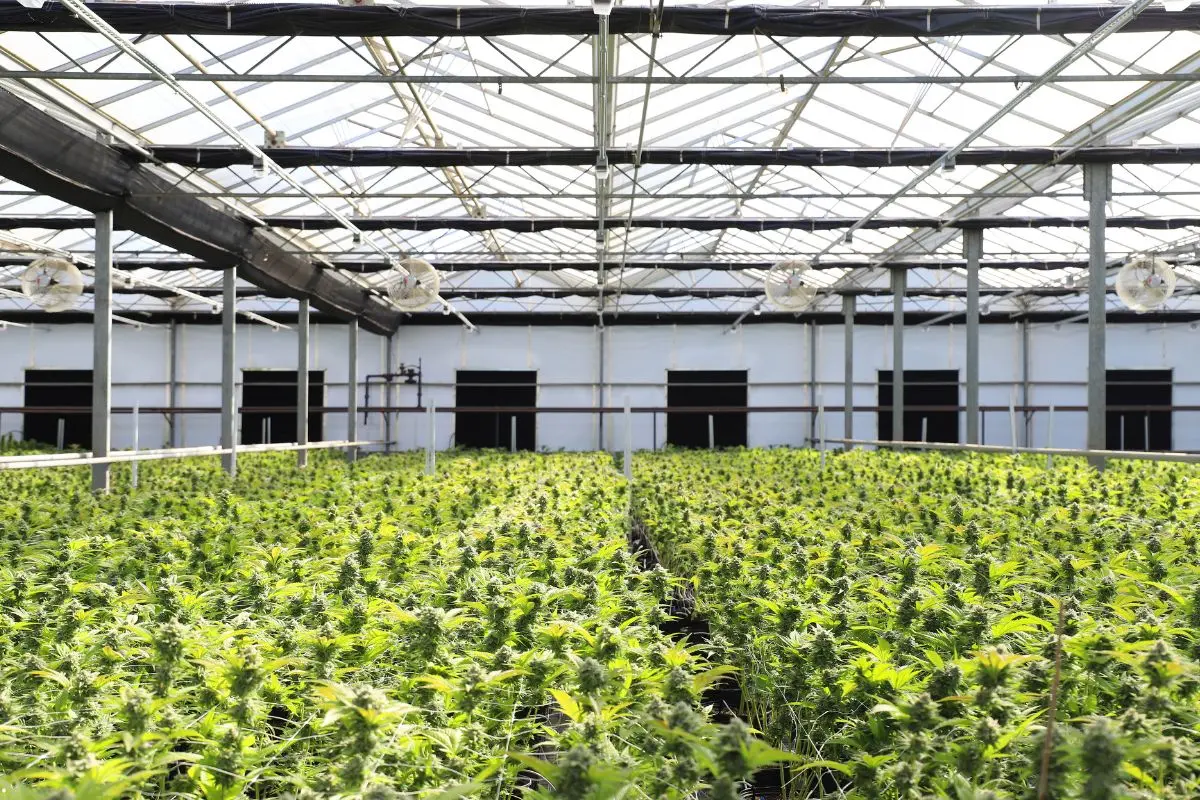

When you first stand before a wall of mature plants ready for cutting, it’s tempting to believe that the hard part is over — that you only need to grab the shears and get to work. In reality, when you have a large number of specimens, a lack of planning can turn this exciting moment into a marathon of chaos, exhaustion, and waste. A crop that’s been maturing for months can lose quality within hours if the harvest is rushed or done in the wrong order.

Experienced growers often say that when working with many plants, you have to think like the conductor of an orchestra: every movement needs to be in sync, and the tempo adjusted to the overall “concert hall.” In this case, the “notes” are the plants’ parameters — trichome maturity, bud structure, even the condition of the leaves. Not all plants, even of the same strain, reach their peak at the same time. Understanding this difference helps avoid the scenario where some buds are overripe while others still need a few more days.

Planning begins long before the first cut. Keeping notes throughout the growth cycle is invaluable: which plants flowered faster, which were slower, what differences appeared in bud density. Large-scale growers sometimes keep “field maps” — layouts of pots or grow sites with the expected harvest order marked. This allows the process to be organized so that each batch is cut at its optimal moment, rather than simply when it happens to be next in line.

The second pillar of planning is preparing the trimming and drying space. With a large number of plants, you can’t expect everything to fit in one room — rotation is essential. If your drying space has limited capacity, it’s better to harvest in batches, keeping a steady rhythm: cut only as much as you can hang or lay out in ideal conditions that same day. The rest should remain in their controlled growing environment until it’s their turn.

It’s also worth remembering that the speed of human work — whether by a team or a solo grower — has limits. Trimming twenty large plants in a day might sound ambitious, but in practice it leads to fatigue, and tired hands mean less precision and more damaged trichomes. Large operations often use schedules similar to factory shifts: several hours of cutting, a break, then another round. It may stretch out the process, but it results in a higher percentage of the harvest staying in prime condition.

Some growers with large numbers of plants also use a “partial harvest” strategy — removing only the main colas at peak ripeness and leaving the lower parts of the plant for a few extra days to finish under the lights. This approach, however, requires close observation and confidence that the remaining parts won’t fall victim to mold during that extra time.

There’s one more element of planning that is often overlooked: the mental aspect. Big harvests aren’t just physically demanding — they carry pressure. Everyone knows the value of those plants and the cost of their growth cycle. A solid plan eases that stress, because you know you’re following a process, and processes are far less likely to derail than random, chaotic action.

Ultimately, a good harvest plan for a large number of plants combines three things: understanding the ripening pace of each plant, realistically adapting logistics and space, and caring for the well-being of the people doing the work. The rest is intuition — the same instinct that tells you, the moment you see the trichomes take on that perfect color, that it’s time.